- Part 1 - In-the-wild Android Kernel Vulnerability Analysis + PoC

- Part 2 - Extending The Race Window Without a Kernel Patch

- Part 3 (this blog post) - Uncovering Chronomaly

In the first blog post, I walked you through my step-by-step process of building a proof-of-concept trigger for CVE-2025-38352. This first proof-of-concept used a kernel patch to extend the race window by 500 ms.

In the second blog post, I showed you how to ditch the kernel patch and extend the race window from userland instead.

In this final post, I'll take you through the entire exploit development process of Chronomaly – from the ideas that failed, to the ideas that worked, and everything in between.

Let's uncover Chronomaly, shall we?

Table of Contents

Exploit and Demo

If you're just here for the Chronomaly exploit, you can find it in the Github repository linked below. It is extremely detailed with tons of comments. I tried simplifying it as much as possible, but it is still incredibly complex, so if you have any questions, feel free to DM me on X.

https://github.com/farazsth98/chronomaly

And a demo:

All the details about setting up the exploit can be found in the repository above.

Introduction

Before you read this post, I highly recommend reading part 1 and part 2 first, as well as @streypaws' blog post here. Reading those will provide you with full context, as this blog post will start where part 2 left off.

I've also structured this blog post to reflect the entire exploit development process as closely as possible. This means that some sections will cover failed ideas and strategies. If you'd prefer to skip ahead, I'll provide a link in each of these sections to jump directly to the section describing the final working strategy.

Additionally, I should point out that the previous blog posts were written with kernel v6.12.33 in mind. I've since switched to v5.10.157, as that more closely resembles the kernel a vulnerable android device would be running.

Recapping Where We Left Off

At the end of part 2, I showcased a working PoC that extended the race window in handle_posix_cpu_timers().

How the PoC Worked

In short, the steps I took to achieve this were as follows:

- Set up 18 stalling timers, and 1 UAF timer (amount of firing timers handled in an interrupt by

handle_posix_cpu_timers()is limited to 19). - Ensure that the timers all fire at the same time.

- Ensure that the stalling timers are "collected" before the UAF timer inside

handle_posix_cpu_timers(). - Each timer sends a

SIGUSR1signal to all threads in the process. - Set up the maximum number of threads possible. Ensure they all block

SIGUSR1, and have them all block execution by reading on a pipe (effectively: sleep without using the CPU). - Set up the racer thread (called "reapee" thread in the previous posts) on a child process responsible for triggering the vulnerability.

- Triggering the vulnerability requires entering

handle_posix_cpu_timer()to handle firing timers afterdo_notify()wakes up the ptracing parent process).

- Triggering the vulnerability requires entering

- Ensure the racer thread is ptraced by the parent process.

- Use

waitpid()in the parent to reap the racer thread. If done correctly, the thread will be reaped right as it is executinghandle_posix_cpu_timers(). - Use

usleep()in the child process to sleep an arbitrary amount of time, and then trigger atimer_delete()on the UAF timer. Theusleep()helps thetimer_delete()land in the race window. - When the timers fire,

send_sigqueue()callscomplete_signal(), which loops through every single thread in the process and checks which one is able to accept this signal.

Effectively, the PoC was creating a little over 11,000 stalling threads, which meant that for each one of the 19 timers being handled by handle_posix_cpu_timers(), complete_signal() would loop ~11,000 times. This ended up extending the race window to 4-5 milliseconds, which was enough time to free the UAF timer and trigger a UAF.

Nothing Is Perfect

Even though the PoC worked, there were still many problems left to solve...

4-5milliseconds does not seem that long. Could I extend the race window even more?- The logic I used to "time" the

timer_delete()was fragile - ideally, there should be a way to know when the racer thread is in the race window insidehandle_posix_cpu_timers(). - Deleting the timer unsets the

SIGQUEUE_PREALLOCflag on thetimer->sigq, which triggers aBUG_ON()insidesend_sigqueue(). I had to figure out a way around that to continue on towards exploitation. - How can we detect whether we won the race and are handling a freed timer inside

handle_posix_cpu_timers()?

Let's now walk through the final exploit development process together.

Making The Race Window Even Longer

My first goal was to maximize the length of the race window.

Enumerating Available Options

I look through every option available to extend the race window. We already know that handle_posix_cpu_timers() will call cpu_timer_fire() for each of the 19 timers it handles. The question is - what methods do we have of increasing the execution time of cpu_timer_fire()?

cpu_timer_fire() calls posix_timer_event(), which only calls send_sigqueue() (code). What options do we have here to extend the race window?

prepare_signal()is called. This function has special handling for stop signals andSIGCONT. In both cases, it will loop over all every thread in the process, similar tocomplete_signal().signalfd_notify()is called to notify any waiters on asignalfdfor this signal.complete_signal()has already been covered before.

complete_signal() has already been covered, so let's take a look at prepare_signal() and signalfd_notify().

Option 1 - prepare_signal()

Looking at prepare_signal() (code), the logic is roughly as follows:

- If this process is in the middle of dying via a group exit, return

sig == SIGKILL. This doesn't apply to us. - If the signal being sent is

SIGSTOP,SIGTTIN,SIGTSTP, orSIGTTOU, it's treated as a stop signal. Iterate over every thread and removeSIGCONTfrom the pending list. - If the signal being sent is

SIGCONT, iterate over all threads to remove each of the four stop signals mentioned above, then wake them up. - Return true if the signal is not currently being ignored, and false otherwise.

Now, since it iterates over all threads in step 2 or 3 (mutually exclusive, both steps can't happen at the same time), we can iterate over all threads once here, and once in complete_signal(). This would effectively double the length of the race window.

But... can we do better?

Option 2 - signalfd_notify()

signalfd_notify() (code) is really simple, it calls wake_up(&tsk->sighand->signalfd_wqh) to wake up any waiters sleeping on the target task's signalfd waitqueue.

Initially, I ignored this function, because I didn't see any loops here. However, once I dove deeper into it, I found that it ends up calling __wake_up_common() (code), which iterates over all waiters on the waitqueue like this:

list_for_each_entry_safe_from(curr, next, &wq_head->head, entry) {

// Handle the waiter

}I noted that a signalfd is just a file descriptor, so it has to be backed by a struct file. Therefore, I looked for cross-references to tsk->sighand->signalfd_wqh, and found that signalfd_poll() calls poll_wait() with the wait_queue_head_t * argument set to current->sighand->signalfd_wqh.

static __poll_t signalfd_poll(struct file *file, poll_table *wait)

{

struct signalfd_ctx *ctx = file->private_data;

__poll_t events = 0;

poll_wait(file, ¤t->sighand->signalfd_wqh, wait);

// [ ... ]

return events;

}

static inline void poll_wait(struct file * filp, wait_queue_head_t * wait_address, poll_table *p)

{

if (p && p->_qproc && wait_address)

p->_qproc(filp, wait_address, p);

}This immediately reminded me of Jann Horn's blog post titled "Racing against the clock -- hitting a tiny kernel race window". In that post, he explains that you can create 500 epoll instances, duplicate one file descriptor 100 times, and then install all 500 epoll instances as watchers on each of the dup'd file descriptors. The final result is that the file descriptor's waitqueue would end up with 500 * 100 = 50,000 waitqueue entries, all of which would need to be notified if a timerfd expired and was handled right inside a race window.

Now, we aren't using a timerfd (the POSIX CPU timer is a struct k_itimer), but since we have a signalfd here being notified, could it work?

I first traced through the code path for epoll_ctl(..., EPOLL_CTL_ADD, ...) to see how it would work. I noticed that it ends up calling vfs_poll() on the struct file *, which ends up calling signalfd_poll() -> poll_wait(). In poll_wait(), p->_qproc has been set to ep_ptable_queue_proc(), which creates a waitqueue entry and inserts it into the wait_queue_head_t * that was passed into it!

Perfect! If I could add 50,000 waitqueue entries, it would make the previous race window over 5 times longer (the wake_up() code path is more complex than just iterating over threads in complete_signal()).

This was implemented like this in the final exploit:

// Set up signalfds for `SIGUSR1` and `SIGUSR2`

sigset_t block_mask;

sigemptyset(&block_mask);

sigaddset(&block_mask, SIGUSR1);

sigusr1_sfds[0] = SYSCHK(signalfd(-1, &block_mask, SFD_CLOEXEC | SFD_NONBLOCK));

sigemptyset(&block_mask);

sigaddset(&block_mask, SIGUSR2);

sigusr2_sfds[0] = SYSCHK(signalfd(-1, &block_mask, SFD_CLOEXEC | SFD_NONBLOCK));

// Block the signals

sigemptyset(&block_mask);

sigaddset(&block_mask, SIGUSR1);

sigaddset(&block_mask, SIGUSR2);

sigprocmask(SIG_BLOCK, &block_mask, NULL);

// Create epoll instances

for (int i = 0; i < EPOLL_COUNT; i++) {

epoll_fds[i] = SYSCHK(epoll_create1(EPOLL_CLOEXEC));

}

// Duplicate sfds, index 0 is the original

for (int i = 1; i < SFD_DUP_COUNT; i++) {

sigusr1_sfds[i] = SYSCHK(dup(sigusr1_sfds[0]));

sigusr2_sfds[i] = SYSCHK(dup(sigusr2_sfds[0]));

}

// Setup epoll watchers now

struct epoll_event ev = {0};

ev.events = EPOLLIN;

for (int i = 0; i < EPOLL_COUNT; i++) {

for (int j = 0; j < SFD_DUP_COUNT; j++) {

ev.data.fd = sigusr1_sfds[j];

SYSCHK(epoll_ctl(epoll_fds[i], EPOLL_CTL_ADD, sigusr1_sfds[j], &ev));

ev.data.fd = sigusr2_sfds[j];

SYSCHK(epoll_ctl(epoll_fds[i], EPOLL_CTL_ADD, sigusr2_sfds[j], &ev));

}

}Note

It is important for the signals to either be blocked, or to have a signal handler installed. Otherwise, the signal will basically act like a

SIGKILL. I found that blocking the signals (and later, draining each signal out of thesignalfdusingread()) was the easiest approach.

Testing this with my kernel profiling patch showed that the race window was now 31-34 milliseconds long! That's a huge improvement!

To simplify the PoC, I removed the ~11,000 threads that I was creating to extend the race window via complete_signal(). The final race window was 24-26 milliseconds on average, which I was happy with.

Onto the next steps!

Deleting The Timer In The Race Window

My second goal was to ensure that I could call timer_delete() on the UAF timer every single time that the race window was entered. Currently, even if I enter the race window, it's possible that my fragile usleep() delay implementation in the child process calls timer_delete() too early (it would not be possible to call it too late due to the 24-26 millisecond race window).

After implementing the signalfd race window extension logic, I suddenly had an epiphany...

When the very first stall timer is being handled in handle_posix_cpu_timers(), it will end up calling signalfd_notify() (explained above). This will wake up any waiters currently polling on the signalfd...

So, why don't I set up a thread that polls on a signalfd created for SIGUSR1 (which is the signal that the stall timers send)? After it wakes up for the first time, if the thread immediately calls timer_delete() on the UAF timer, the deletion is guaranteed to happen in the race window!

I implemented this logic in the free_timer_thread, which calls the free_func() handler function:

void free_func(void) {

// [ ... ]

struct pollfd pfd = {

.fd = sigusr1_sfds[0],

.events = POLLIN

};

// Poll for SIGUSR1.

for (;;) {

int ret = poll(&pfd, 1, 0);

// Got SIGUSR1 from the first stall timer, in race window now.

if (pfd.revents & POLLIN) {

SYSCHK(timer_delete(uaf_timer));

break;

}

// [ ... ]

}

}The entire purpose of this function (at the time) was to be woken up by the first stall timer's SIGUSR1 signal, immediately delete the UAF timer, and then exit.

Funnily enough, using this caused this warning in timer_wait_running() (code) to be hit many times:

static struct k_itimer *timer_wait_running(struct k_itimer *timer,

unsigned long *flags)

{

// [ ... ]

if (!WARN_ON_ONCE(!kc->timer_wait_running))

kc->timer_wait_running(timer);

// [ ... ]

}This function is called by timer_delete() if posix_cpu_timer_del() ever returns TIMER_RETRY, which will happen if the following conditions are met:

- Timers are currently being handled by

handle_posix_cpu_timer(). - We did not enter

handle_posix_cpu_timers()afterexit_notify(), therefore the task was not able to be reaped by the ptracing parent process. posix_cpu_timer_del()notices that the timer is currently firing, and so returnsTIMER_RETRY.timer_delete()callstimer_wait_running().

In this case, the kc->timer_wait_running function pointer is NULL for POSIX CPU timers created using CLOCK_THREAD_CPUTIME_ID (which this exploit requires).

I found this quite funny. It's a harmless little bug, but it actually implies that the kernel developers made an invalid assumption here – that POSIX CPU timers cannot ever return TIMER_RETRY when the timer related system calls are called on them. Obviously, this assumption is wrong, but I digress.

Alright, we've extended the race window, and we've implemented race window detection logic that guarantees that the UAF timer is always deleted inside the race window.

What's next?

Slight Detour - A Failed Idea

You can skip ahead to the next section by clicking here.

Initially, I noticed that the struct k_itimer is not immediately freed, but instead freed via RCU (code):

static void release_posix_timer(struct k_itimer *tmr, int it_id_set)

{

// [ ... ]

call_rcu(&tmr->rcu, k_itimer_rcu_free);

}

static void k_itimer_rcu_free(struct rcu_head *head)

{

struct k_itimer *tmr = container_of(head, struct k_itimer, rcu);

kmem_cache_free(posix_timers_cache, tmr);

}When I noticed this, the first idea I had was to try and extend the race window long enough for this timer to be fully freed via RCU. However, no matter what I did, the RCU free would just refuse to occur in the race window. I even implemented full cross-caching for struct k_itimer before I realized the timer wasn't being freed.

I ended up scrapping this idea. In hindsight, this made no sense anyway, because even if I succeeded down this route, I'd have to find an object that satisfied the following conditions:

- Has a valid pointer at the

timer->sigqoffset. - Has a valid

spin_lockat thetimer->it_lockoffset. - The memory pointed to by

timer->sigqmust have theSIGQUEUE_PREALLOCflag set at thetimer->sigq->flagsoffset. - Probably a few other conditions I'm missing...

Basically, it seemed extremely unlikely that this was the right path to exploitation. So after wasting many hours on this, I finally moved on and decided to target the timer->sigq object instead, which is freed immediately through release_posix_timer() rather than via RCU.

Dodging The BUG_ON()

The subsections below this section will describe some failed ideas. If you'd like to skip ahead to the working strategy, choose one of the following options:

- Working strategy, but still triggers the

BUG_ON()sometimes – click here. - Fully working strategy, dodges the

BUG_ON()completely - click here.

The BUG_ON()

In send_sigqueue() (code), this is the BUG_ON() we're hitting, where q is the timer->sigq object.

BUG_ON(!(q->flags & SIGQUEUE_PREALLOC));Looking for cross-references to SIGQUEUE_PREALLOC, we can see that it's set when do_timer_create() allocates a sigqueue object for timer->sigq by calling sigqueue_alloc() (code):

struct sigqueue *sigqueue_alloc(void)

{

struct sigqueue *q = __sigqueue_alloc(-1, current, GFP_KERNEL, 0);

if (q)

q->flags |= SIGQUEUE_PREALLOC;

return q;

}And subsequently, when a timer is deleted via timer_delete(), release_posix_timer() will call sigqueue_free(), which does two things (code):

- It unconditionally removes the

SIGQUEUE_PREALLOCflag from thetimer->sigq. - It frees the

timer->sigqonly if it is not in some task's pending list (it will be added to a pending list insend_sigqueue()).

void sigqueue_free(struct sigqueue *q)

{

// [ ... ]

q->flags &= ~SIGQUEUE_PREALLOC;

// [ ... ]

}So, the issue is obvious – when we free the timer in the race window via timer_delete(), this SIGQUEUE_PREALLOC flag is removed, which now triggers the BUG_ON() when the same timer's sigq is passed into send_sigqueue().

So, what can we do to dodge the BUG_ON()?

First Idea - Re-allocate Another Timer

My first idea was to just re-allocate another timer while in the race window. Since this timer will also allocate its own timer->sigq, if we can get the timer to reuse the uaf_timer->sigq's memory for this, we can reset the SIGQUEUE_PREALLOC flag and dodge the BUG_ON() entirely.

This is doable due to how the SLUB allocator works. Without going into too many details (this blog post is already going to be long enough...), the following steps can be taken to ensure that the uaf_timer->sigq is easily re-allocated by another timer:

- Pin to a specific CPU (I use CPU 3) when allocating the

uaf_timer. - Ensure no other

sigqueueallocations occur on this CPU after this point. This leaves theuaf_timer->sigqon an "active" slab page. - When the

uaf_timeris freed in the race window, thetimer->sigqis queued to the head of the active slab page's freelist. - When

realloc_timeris allocated now,sigqueue_alloc()will use the entry at the head of the active slab page's freelist to satisfy the allocation. This just so happens to beuaf_timer->sigqafter the above step.

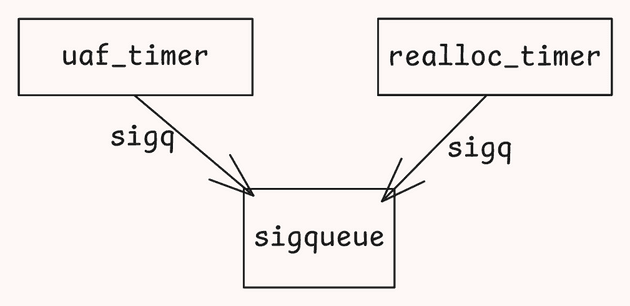

Note

uaf_timeris the UAF timer, andrealloc_timeris the re-allocated timer whose->sigqreuses the same memory asuaf_timer->sigq.

As long as the free and reallocation happens on the same CPU, and step 2 is followed, the realloc_timer->sigq will be guaranteed to reuse the same memory as uaf_timer->sigq.

But what does this really achieve? The realloc_timer->sigq just ends up on the target task's pending (or shared_pending) list as a signal. For all intents and purposes, this is an allocated signal, there's no memory corruption that could occur here...

Remember this idea from here on out, because the working strategy actually follows on from this! 😉

First Idea - Potential Race Win Detection Mechanism?

One thing I realized when implementing the PoC for this though, is that the realloc_timer->sigq could actually be set to use a different signal! So, we can actually take the following steps to detect if we hit the race window and successfully re-allocated uaf_timer->sigq:

- Set up all 19 timers (18 stall timers plus the UAF timer) to fire a

SIGUSR1signal to the thread group. - In the race window, free and reallocate the UAF timer, but set the reallocated timer's signal to

SIGUSR2instead. - Poll on a

signalfdforSIGUSR2. If it's received, the timer was successfully reallocated (send_sigqueue()saw the re-allocatedtimer->sigqthat sendsSIGUSR2), and the race was won. - If no

SIGUSR2is observed, the race was lost.

This was actually the race win detection mechanism I implemented in the final exploit. More on that later!

Second Idea - Re-allocate As struct msg_msg

This idea began when I noticed that struct sigqueue's list_head pointers are at offset 0. I looked for other structures that also have list_head pointers at offset 0 and ended up landing on struct msg_msg. The goal was to type-confuse a struct msg_msg as a struct sigqueue and have it be inserted into the target task's pending list.

I compared struct sigqueue (code) with struct msg_msg (code) and found the following:

- The

list_headpointers are at offset 0. sigqueue->flagsoffset matchesmsg_msg->m_type, which is controllable from userland! SoSIGQUEUE_PREALLOCcan be set.

This looked perfect, I could use the cross-cache exploitation technique to free the UAF sigqueue's slab page back to the page allocator, and re-allocate it as a page of struct msg_msg objects to gain a type-confusion primitive!

... Right?

Well, no. There are quite a few problems with this approach. And, as usual, it took me many hours to figure all this out 😅

The first issue is that the list_head->next pointer is set to NULL when a struct msg_msg is allocated (code). Additionally, this list_head is only ever inserted into a list, or deleted via list_del() (instead of list_del_init(), which deletes and marks the list as empty).

This is all major problem because the send_sigqueue() function has a !list_empty() check, which will fail unless list_head->next == &list_head (code):

int send_sigqueue(struct sigqueue *q, struct pid *pid, enum pid_type type)

{

// [ ... ]

if (unlikely(!list_empty(&q->list))) {

// [ ... ]

goto out;

}

// [ ... ]

out:

// [ ... unlock sighand lock and return ... ]

}

static inline int list_empty(const struct list_head *head)

{

return READ_ONCE(head->next) == head;

}In this case, for a struct msg_msg, this condition is never true (i.e the list will never be empty).

Unfortunately, as luck would have it, this was the last thing I figured out 😅

The other issue is subtle – struct msg_msg is allocated out of normal kmalloc-X caches in kernel v5.10.157. These caches can be anywhere between kmalloc-64 all the way up to kmalloc-1k or kmalloc-2k (not sure what the maximum size of a struct msg_msg can be).

Each allocation out of a kmalloc-X cache will always use X bytes in the page, even if the actual object doesn't use X bytes. For example, a 48 byte object would be allocated out of kmalloc-64 and use 64 bytes for each allocation. The slab sizes themselves can be fetched like this:

/ # cat /sys/kernel/slab/kmalloc-64/slab_size

64

/ # cat /sys/kernel/slab/kmalloc-96/slab_size

96The problem here is that struct sigqueue is allocated out of a specific kmem_cache named sigqueue_cachep. The size of the struct sigqueue is 80 bytes. You would expect that the slab size would be 96 bytes for this, right?

/ # cat /sys/kernel/slab/sigqueue/object_size

80

/ # cat /sys/kernel/slab/sigqueue/slab_size

80Well, that's a bummer. What this means is that even if we re-allocate the UAF sigqueue over with a page of struct msg_msg objects, there's no guarantee that a struct msg_msg object will land exactly where our UAF sigqueue is allocated. The Android kernel also has CONFIG_SLAB_FREELIST_RANDOM=y set, which prevents us from being able to control where in the page the uaf_timer->sigq will be allocated.

After solving some LLM-assisted math problems to figure out if this option was viable at all (trying to align 80 byte allocations with 16, 32, 64, 96, 128, and 256 byte object allocations in a slab page), I concluded that this idea is not reliable enough at all to work in an exploit.

So... Onto another idea!

Third Idea - A Second Tinier Race Window?

It was at this moment that I suddenly realized something critical from the first idea. Since the struct k_itimer is freed via RCU later, we actually end up in a situation like this after the timer is re-allocated:

The important point here is that uaf_timer->sigq == realloc_timer->sigq, but uaf_timer != realloc_timer.

Why does this matter? Because their ->it_locks are different!

If we successfully re-allocate the uaf_timer as a realloc_timer, when handle_posix_cpu_timers() acquires the timer->it_lock (code), it will actually be acquiring uaf_timer->it_lock, because that's what was collected in the local firing list!

This leaves realloc_timer->it_lock un-acquired, which crucially opens up a second race window right inside send_sigqueue() (code):

int send_sigqueue(struct sigqueue *q, struct pid *pid, enum pid_type type)

{

// [ ... ]

BUG_ON(!(q->flags & SIGQUEUE_PREALLOC));

// [ ... race window starts ... ]

ret = -1;

rcu_read_lock();

t = pid_task(pid, type);

// [ ... race window ends ... ]

if (!t || !likely(lock_task_sighand(t, &flags)))

goto ret;

// [ ... ]

}The race window starts right after the BUG_ON(). In this race window, uaf_timer->it_lock is held, but we can still call timer_delete() on realloc_timer, whose it_lock is not held. This would free the realloc_timer->sigq in the same way (in this case, realloc_timer is not marked as firing as it is allocated using kmem_cache_zalloc()).

But... This race window is extremely short, and there is no way to extend it. We're already in a scheduler interrupt, so we can't trigger another one in the window, and neither rcu_read_lock() nor pid_task() do anything that can consume a controlled amount of CPU time.

Still, I patched in a 500 millisecond delay into the race window, and modified my free_timer_thread to do the following:

void free_func(void) {

// [ ... ]

struct pollfd pfd = {

.fd = sigusr1_sfds[0],

.events = POLLIN

};

// Poll for SIGUSR1.

for (;;) {

int ret = poll(&pfd, 1, 0);

// Got SIGUSR1 from the first stall timer, in race window now.

if (pfd.revents & POLLIN) {

SYSCHK(timer_delete(uaf_timer));

// re-allocate `uaf_timer->sigq`

SYSCHK(timer_create(/* ... */, &realloc_timer));

// Sleep 250ms to be inside our patched race window for sure

usleep(250 * 1000);

SYSCHK(timer_delete(realloc_timer));

break;

}

// [ ... ]

}

}Running the PoC in this state, I could confirm that the freed uaf_timer->sigq was being inserted into the target task's pending list (using GDB to inspect sigqueue_cachep->offset of the uaf_timer->sigq. Slab freelist pointers are inserted at this offset if the object is freed).

Tip

When creating a timer, you can set the

struct sigevent's.sigev_value.sival_ptrto a unique value (say,0x4141414141414141). Then, you can add a kernel patch that checks for this value insidedo_timer_create(), and subsequentlyprintk()the address of the allocatedtimer->sigqfor debugging purposes. You'll find some lines commented out in my final exploit that does exactly this. 😉

The issue at this point is not the tiny race window, but the BUG_ON(). If that BUG_ON() wasn't there, I could repeat this step many times and adjust the delay to hit the tiny window at some point.

Note

I actually managed to hit this race window quite a few times during my testing without the artificial delay from the kernel patch. It was unreliable, and it hit the

BUG_ON()just as many times as it won the race, but hey, it worked!

However, since CPU consumption is never 100% stable, calling timer_delete(realloc_timer) too early was all but inevitable, so this approach would not really work for the final exploit.

So... I spent many hours testing for ways to increase the race window.

One of the things I tried was to use the same signalfd_notify() trick to wake up another thread while send_sigqueue() is running, and have that thread call timer_delete(realloc_timer). Since signalfd_notify() is called before the realloc->sigq is added to the task's pending list, there should hopefully be enough time to wake up another thread and have it free the realloc_timer->sigq before signalfd_notify() is able to return.

But this wasn't working... For some reason, sigqueue_free() was failing to acquire the task->sighand->siglock until handle_posix_cpu_timer() was releasing it.

Tip

I figured out this locking issue by inserting

printk()statements intosigqueue_free()andsend_sigqueue().

But isn't the target task different? Why would the lock fail to acquire?

It was at this point that I learned that the task->sighand structure is actually shared across all threads in a process! And in this case, since the lock_task_sighand() in send_sigqueue() is acquiring the sighand lock of the target task, there is no way for any other thread in that process to wake up and also delete the timer.

Note

POSIX CPU timers are bound to the process that they're created in. This means that other threads in the same process can call

timer_settime()/timer_delete()/ etc on them, but a different process would not be able to.

If I remember correctly, it was almost 5 AM when I made this realization. I decided to head to bed and continue the next day.

As is usually the case, I started connecting a million different dots in my head while falling asleep... And one of those ideas just happened to lead me to the strategy I used in the final exploit!

Fourth Idea - Double Insertion

The Linux kernel's linked list implementation is an "Intrusive Linked List". I highly recommend reading the linked article if you haven't come across this before.

The most important point regarding intrusive linked lists is this:

Important

Never allow the same object reference to be in more than one linked list at any given time, including itself!

In fact, the !list_empty() check in send_sigqueue() is there for this exact reason:

int send_sigqueue(struct sigqueue *q, struct pid *pid, enum pid_type type)

{

// [ ... ]

if (unlikely(!list_empty(&q->list))) {

// [ ... ]

goto out;

}

// [ ... ]

out:

// [ ... unlock sighand lock and return ... ]

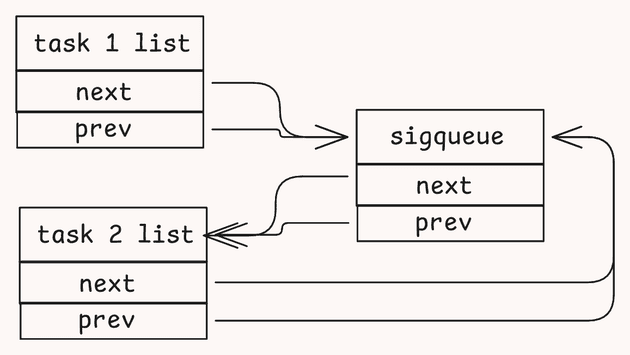

}The following diagram illustrates what a double-inserted struct sigqueue would look like in memory (assume it's inserted into task 1 first, then into task 2, and there are no other signals in the pending lists):

Essentially, we have a situation where the struct sigqueue thinks it is in task 2's pending list, while both task 1 and task 2 think that the struct sigqueue is in their pending list.

The issue occurs later when this struct sigqueue is removed from the pending list (for example, by calling read() on a signalfd). The collect_signal() function is used to dequeue the struct sigqueue (code), which uses list_del_init() to remove the struct sigqueue from the actual pending list, before calling __sigqueue_free() on it to free it.

static void collect_signal(int sig, struct sigpending *list, kernel_siginfo_t *info,

bool *resched_timer)

{

// [ ... ]

still_pending:

list_del_init(&first->list);

// [ ... ]

if (first) {

__sigqueue_free(first);

} else {

// [ ... ]

}

}The logic of list_del_init() is as follows:

- Set

sigqueue->next->prev = sigqueue->prev. - Set

sigqueue->prev->next = sigqueue->next. - Set

sigqueue->next = &sigqueueandsigqueue->prev = &sigqueue.

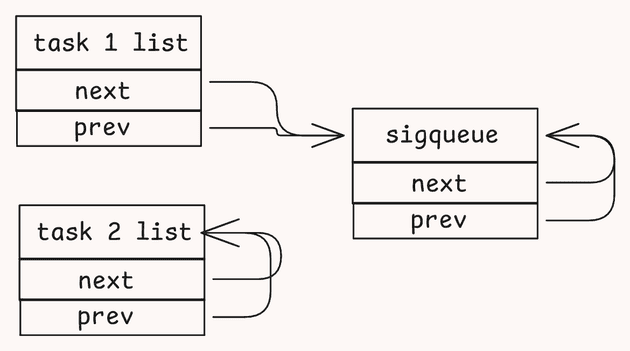

Looking back at the above diagram, the problem is obvious - no matter which list dequeues this struct sigqueue, the pointers in task 1's pending list will never be updated. Additionally, since the .next and .prev pointers of the struct sigqueue are updated to point back to itself, this struct sigqueue will now end up forever stuck inside task 1's pending list (possibly as a freed object if __sigqueue_free() freed it)!

The following diagram illustrates this scenario:

So, after sleeping and letting my brain connect all these dots together, I finally came up with the following plan:

- Get into the race window and free the

uaf_timer– same as before. - Instead of reallocating

realloc_timer->sigqin the same process, communicate to a different process (in my exploit, the "parent" process) to re-allocaterealloc_timer->sigq(must be on the same CPU since slab freelists are per-CPU based). - Ensure that the

realloc_timer->sigqfires aSIGUSR2signal, so we can detect whether we won the race. - In the parent process, use

usleep()to sleep for a configurable amount of time to allow the child process to entersend_sigqueue()with theuaf_timer->sigq. This configurable time is modified byPARENT_SETTIME_DELAY_US_DELTAon each retry if the race fails. - In the parent process after the sleep, immediately call

timer_settime(realloc_timer)with theTIMER_ABSTIMEflag, and astruct itimerspecset to fire in the past. - Since the time is set in the past, it will cause

cpu_timer_fire()to be called immediately insideposix_cpu_timer_set()(code). - If the parent process sleeps just the right amount of time, the child process should be inside

send_sigqueue()with theuaf_timer->sigq.

At this point, both processes will enter send_sigqueue() while the following locks are held:

- Child process

uaf_timer->it_lock- Own process's

sighand->siglock.

- Parent process

realloc_timer->it_lock- Own process's

sighand->siglock

As you can tell, all of these locks are different, so there is no issue with both the parent and child processes running concurrently in send_sigqueue().

The only other thing that must be prepared in the child process is to attach 50,000 epoll waiters to the signalfd for SIGUSR2 as well. This ensures that this second race window is extended, because the child process will call signalfd_notify() before queueing to its own task's pending list (code), and signalfd_notify() will take a decent chunk of time to wake up all 50,000 epoll waiters.

Important

The other reason for using

timer_settime()to perform a double insertion instead of just deleting the timer in the (now slightly longer) race window is that it prevents theBUG_ON()from ever being hit accidentally.

This implementation can be seen in the current exploit (omitting a lot of code for brevity). The free_func() thread deletes the uaf_timer as soon as it sees a SIGUSR1 signal, and then communicates to the parent process via a pipe. The parent process then re-allocates realloc_timer, sleeps for parent_settime_delay, and then calls timer_settime() with a time in the past:

// In child process's `free_func()` thread

for (;;) {

int ret = poll(&pfd, 1, 0);

// Got SIGUSR1 from the first stall timer, in race window now.

if (pfd.revents & POLLIN) {

SYSCHK(timer_delete(uaf_timer));

// Change CPUs so the parent process can continue using our

// CPU to re-allocate the same `uaf_timer->sigq`.

pin_on_cpu(0);

SYSCHK(write(exploit_child_to_parent[1], SUCCESS_STR, 1)); // sync 4.SUCCESS

// Barrier used for unrelated synchronization

pthread_barrier_wait(&barrier); // barrier 4

break;

}

}

// In parent process, pin to the same CPU as the `uaf_timer` was freed on,

// then wait for the child to tell us to re-allocate.

pin_on_cpu(3);

SYSCHK(read(exploit_child_to_parent[0], &m, 1)); // sync 4

if (m == SUCCESS_CHAR) {

// reallocate

SYSCHK(timer_create(CLOCK_THREAD_CPUTIME_ID, &realloc_evt, &realloc_timer));

// configurable sleep time

usleep(parent_settime_delay);

// Call `cpu_timer_fire()`

SYSCHK(timer_settime(realloc_timer, TIMER_ABSTIME, &fire_ts, NULL));Quick Disclaimer - Exploit Complexity

At this point, the exploit is approaching some really high levels of complexity, mostly due to the bug being a race condition, and how much the parent and child processes need to communicate to make the exploit work.

Unfortunately, I will not be able to explain the exploit line-by-line in the same way that I did with the PoCs in the previous posts. To be completely honest, I still have a difficult time explaining my own exploit to myself... even though I commented it so well! 😅

The best way to understand the exploit would be to read through this blog post, then read through my exploit, and rewrite it in your own way, synchronizing the processes in a way that works for you.

However, if you have questions about any specific parts of my exploit, feel free to DM me on X, and I'll try my best to help you!

Which List Am I In?

At this point, remember that the realloc_timer was set to fire by the parent process. Assuming that realloc_timer->sigq == uaf_timer->sigq, there are four possible outcomes:

- We won the 2nd race –

realloc_timer->sigqis inserted into the parent process first, then the child process. - We won the 2nd race –

realloc_timer->sigqis inserted into the child process first, then the parent process. - We lost the race – parent process called

timer_settime()too early, so the parent process succeeded, but the child process failed to insert it into its own list. - We lost the race – parent process called

timer_settime()too late, so the parent process failed, but the child process succeeded in inserting it into its own list.

Problem: How can we figure out which of these four situations we're in?

Lost The Race - Too Early or Too late?

First, let's take a look at scenarios 3 and 4, as they're easier to explain. Keep in mind – we're already detecting that our free -> re-allocation was triggered successfully by polling for SIGUSR2 in the child process.

In send_sigqueue(), if the !list_empty() check fails, take a look at what happens (code):

int send_sigqueue(struct sigqueue *q, struct pid *pid, enum pid_type type)

{

// [ ... ]

if (unlikely(!list_empty(&q->list))) {

BUG_ON(q->info.si_code != SI_TIMER);

q->info.si_overrun++;

result = TRACE_SIGNAL_ALREADY_PENDING;

goto out;

}

// [ ... ]

out:

// [ ... ] unlock and exit

}The line q->info.si_overrun++ is the key! It's a primitive we can use to detect whether we lost the race by calling timer_settime() too early, or too late.

To explain how this works, consider the fact that the parent process is calling timer_settime() and causing the timer to fire immediately. In this case, there is only one scenario where realloc_timer->sigq (using SIGUSR2) won't be queued into the parent process's pending list: It got queued into the child process's pending list too early, meaning timer_settime() was called too late.

Therefore, we can detect scenario 3 in the following way:

- After

timer_settime()is called by the parent process and the timer fires, ask the child process to poll forSIGUSR2. - If the child process receives

SIGUSR2, it means therealloc->sigqwas queued into the child process's pending list. Send "success" to the parent process.- Right now, the 2nd race is potentially won.

- If the child process didn't receive

SIGUSR2, then the race is lost for sure. Send "fail" to the parent process.- At this point, either our original free -> re-allocation failed, or the child process failed to insert the

uaf_timer->sigqbecause the parent process calledtimer_settime()too early and inserted it already. - Either way, the parent process will have

SIGUSR2in its pending list, because it's the one that fired it.

- At this point, either our original free -> re-allocation failed, or the child process failed to insert the

- If the parent process receives "success", check for

SIGUSR2.- If the parent process received

SIGUSR2as well, the race was successfully won. Therealloc_timer->sigqis now in both the child and parent process's pending list. - If the parent process didn't receive

SIGUSR2, thentimer_settime()was called too late. The child process already inserted it before the parent process could get past the!list_empty()check insend_sigqueue().

- If the parent process received

Crucially, for step 3 above, in order to differentiate between the parent process calling timer_settime() too early, and the original free -> re-allocation failing (due to handle_posix_cpu_timers() not being called at the right time), we use the q->info.si_overrun++ primitive from above.

The basic idea is this:

- If the free -> re-allocation failed, then we failed to trigger any UAF, so no matter what, the

realloc_timer->sigqwill only ever be queued to the parent process's list, and the child process will never see it.- This will cause its

si_overrunfield to be 0, because no other process tried to also queue it.

- This will cause its

- If the free -> re-allocation succeeded, but the child still fails to see

SIGUSR2, then it must mean that the child tried to queue it to its own pending list, but failed the!list_empty()check insend_sigqueue().- This will cause the child to increment the

si_overrunfield to 1, which the parent can detect.

- This will cause the child to increment the

If the parent process sees that the child process didn't receive SIGUSR2, it can now check si_overrun. If it sees that it is greater than 0, then it must mean that timer_settime() was called too early. It can now increase the parent_settime_delay (the amount of microseconds it sleeps for before calling timer_settime()) for the next retry.

As for step 4 above, if the parent fails to see the SIGUSR2 after the child has seen it, it means timer_settime() was called too late, so the parent_settime_delay must be reduced for the next retry.

So, that covers the "lost race" scenarios 3 and 4 from above. Now, how do we detect which way we won the race?

Won The Race - List Detection

Once the parent and child have both seen the SIGUSR2 signal, we know we won the race for sure. Now it's time to figure out where the realloc_timer->sigq->list pointers are pointing to – is it the parent's pending list or the child's pending list?

In order to detect this, I came up with the following strategy:

- In the parent, first call

timer_delete(realloc_timer).- This will free the timer, but not

realloc_timer->sigq, since it's part of a task's pending list. - From here on out,

realloc_timer->sigqwill be referred to as theuaf_sigqueue.

- This will free the timer, but not

- Now, use

signalfd_read()on the parent process to dequeue theuaf_sigqueue.- If the

uaf_sigqueue->listpointers point to the parent process, the parent process will lose its reference to theuaf_sigqueuein its pending list. - And vice versa for the child process.

- If the

Going back to that double insertion example, the following two diagrams demonstrate what will happen. First, after the double insertion:

And then, after the dequeue:

Tip

It does not matter which task dequeues the

struct sigqueue, it only matters what thestruct sigqueue'slistpointers are set to. The end result will always be the same.

At this point, the parent process can poll() for SIGUSR2 one last time. If it still detects the signal, then that means that the uaf_sigqueue->list pointers used to point to the child process's pending list. Now the parent process can infinitely free this uaf_sigqueue.

Note

In this case, referring to the diagram above, the parent process is task 1.

If the parent process does not detect the SIGUSR2, it means that the uaf_sigqueue->list pointers used to point to the parent process's pending list. Now the child process can infinitely free the uaf_sigqueue.

Important

It's very important to figure this out, because our only reference to the freed

uaf_sigqueueis via the task's pending list. If we can't figure out which process's pending list theuaf_sigqueueis in, we can't proceed.

One more thing to note – after the parent dequeues the uaf_sigqueue via signalfd_read() in step 2 above, the uaf_sigqueue is freed. This happens because we deleted realloc_timer beforehand.

Cross-caching Back To The Page Allocator

This is the point in my exploit where second_stage_exploit() is called.

I won't go too in-depth into the cross-cache exploitation technique, as it has been covered in many other articles and blog posts. Please refer to the following functions and their callsites in the exploit for more details:

sigqueue_crosscache_preallocs()– Perform pre-allocations before theuaf_timeris allocated.sigqueue_crosscache_postallocs()– Perform post-allocations after theuaf_sigqueueis dequeued and freed.free_crosscache_sigqueues()– Free the pre-allocations and post-allocations in a specific order to send theuaf_sigqueue's slab page back to the page allocator.

Tip

You can use GDB GEF's

xslab -r <addr>command to find the address of thestruct page *for a specific slab allocation.

Tip

You can set a breakpoint on

discard_slab()and compare thepageargument to thestruct page *address of the slab allocation you are trying to free back to the page allocator. This can help you debug your cross-cache implementation.

Getting Heap Leaks

Since sigqueue_cachep allocates order-0 pages, I decided to re-allocate the uaf_sigqueue page as a pipe buffer data page (the page where data is written to when calling write() on a pipefd).

Tip

You can set a conditional breakpoint on

prep_new_page()(b prep_new_page if page == <target_alloc_page_addr>) that you can use to determine exactly how your target page is being allocated. This can help you debug your cross-cache implementation by checking the backtrace after this breakpoint is hit.

When the pipe buffer data page is allocated, it is zeroed out (the page allocator does this automatically). Our goal is to get some heap pointers inserted into this page so we can read it out of the pipe.

Since we know our uaf_sigqueue is in the pipe buffer data page, we actually have a way to leak all of the following addresses:

- Address of another real

struct sigqueue. This will be referred to as theother_sigqueue. - Address of the task's pending list that has a reference to

uaf_sigqueue. - Address of our own

uaf_sigqueue– useful if we have to fake objects in the kernel heap since we control the contents of this entire page.

Note

Although my exploit leaks all three of these addresses, only the address of

other_sigqueueis required to complete the exploit. So my exploit can be simplified in this regard!

For (1), we can just send a real-time signal (SIGRTMIN+1 in my exploit, also other_sigqueue) to the task. It will get queued to the end of the list. Since pending->list.prev == uaf_sigqueue, uaf_sigqueue->list.next will be set to the real-time signal's struct sigqueue object's address. We can read this out of the page using read() on the UAF pipe (scan through the page for the first byte that is not NULL).

For (2), we actually have to go all the way back to the beginning of the exploit, and queue a real-time signal into our process's pending list before we ever started (SIGRTMIN+2 in my exploit). Then, uaf_sigqueue will be queued to the list later (double inserted).

Finally, once we leak the other_sigqueue's address (explained above), we can set uaf_sigqueue->list.next = &other_sigqueue (using write() on the UAF pipe) to set up the list like this:

pending_list -> SIGRTMIN+2 -> uaf_sigqueue -> other_sigqueue -> pending_listAt this point, we can dequeue the SIGRTMIN+2 signal using signalfd_read(). This will cause uaf_sigqueue->list.prev to be set to &pending_list, and we can read this out of the page using the UAF pipe.

After the above, our current list setup is like this:

pending_list -> uaf_sigqueue -> other_sigqueue -> pending_listAt this point, if we set uaf_sigqueue->list.prev and uaf_sigqueue->list.next to both be equal to other_sigqueue, we can dequeue uaf_sigqueue via signalfd_read() while still leaving a reference to it in the task's pending list.

This dequeueing will end up calling list_del_init() on uaf_sigqueue (code), which will set uaf_sigqueue->list.prev = uaf_sigqueue->list.next = &uaf_sigqueue.

At this point, we can use the UAF pipe to read uaf_sigqueue's address from itself.

In my exploit, the following output is shown for the leaks:

[+] Stage 2 - Cross-cache the UAF sigqueue's slab

[+] Reallocated UAF sigqueue slab as a pipe buffer data page

[+] Cleaning up all cross-cache allocations to prepare for next cross-cache

[+] Preparing task pending list for heap leaks

[+] Heap leaks:

- UAF sigqueue page offset 0x500

- Other sigqueue 0xffff9da44507a550

- Task pending list addr 0xffff9da4412b1710

- UAF sigqueue address 0xffff9da443420500Caution

When leaking the

uaf_sigqueue's address above, it actually corruptsother_sigqueue'slistpointers (they both point back to&other_sigqueue, even though the task pending list's.prevpointer is also set to&other_sigqueue).

Exploitation Primitives

I decided to take a little bit of a break and actually consider what primitives we have with our uaf_sigqueue. We already know we can dequeue it an infinite number of times, but what does that actually let us achieve?

Looking at all uses for a struct sigqueue in the kernel, there honestly... isn't a lot. There are basically four potentially useful things that are done with them:

- Get queued into a task's pending list.

- Get dequeued from a task's pending list.

- Get freed.

- Some fields are incremented / decremented / written to (for example,

q->info.si_overrun++insend_sigqueue()).

Dequeueing Into Type Confusion

For the next few hours, my goal was the following – use cross-cache again to free other_sigqueue's slab page back to the page allocator, and re-allocate it as some other object type. Then, set up our uaf_sigqueue->list pointers to point at it, and dequeue to get the other object type inserted into the task's pending list as a struct sigqueue object.

However, as I just explained above, there is not a whole lot that a struct sigqueue is used for. At best, it seemed like I could possibly free the other object, but it would require the object to meet the following conditions:

- I must be able to control 8 bytes at offset 0 (

sigqueue->list.next) and set it to the same task's pending list's address. - It must have a valid writable kernel pointer at offset 72 (

sigqueue->user). - Freeing it must not be affected by that pointer at offset 72.

- The value at offset

sigqueue->info.signomust be settable to a signal number currently pending on the task's pending list (otherwisecollect_signal()will never be called to free it).

This would, in theory, give us an arbitrary free primitive – by linking a different object to the task pending list as a struct sigqueue, and then dequeueing it, we could essentially exploit a UAF on another object!

However, not only does it sound very complicated, but after looking through a lot of structures, I was not able to find one that satisfied all of these conditions.

Now, I wasn't using any specific methodology to look for these structures – I was just manually scanning through potential kernel structures that I know would be useful to gain a UAF on, but after the first pass over a bunch of potential structures, I realized that:

- The conditions are too strict.

- Even if I am able to find a structure that satisfies all four conditions, there's no guarantee that exploiting a UAF on that object would be easy.

At this point, I gave up, because I was not about to go through all of this trouble just to end up having to exploit yet another difficult UAF on a different target.

But something good did come out of this – as I was scanning through structures, I also ended up looking at __sigqueue_free() a bit closer and realized that we actually had a very useful primitive inside of it!

The Arbitrary Decrement Primitive

The __sigqueue_free() function actually gives us an arbitrary decrement primitive (code):

static void __sigqueue_free(struct sigqueue *q)

{

if (q->flags & SIGQUEUE_PREALLOC)

return;

if (atomic_dec_and_test(&q->user->sigpending))

free_uid(q->user);

kmem_cache_free(sigqueue_cachep, q);

}It decrements q->user->sigpending. With our UAF pipe buffer page, we already have full control over q->user, and the sigpending field is at offset 8 in the q->user structure.

So, by setting q->user to target_addr - 8, we can decrement whatever value is there (it's an atomic_t, which is a 4 byte int)!

Immediately, since I had KASLR turned off at this point, I decided to try to decrement the first byte of &core_pattern by setting uaf_sigqueue->user = &core_pattern - 8, and sure enough, it went from "core" to "bore", confirming that the idea works.

Fishing For a Kernel Text Leak

Little bit of a spoiler – but a kernel text leak was not necessary to finish the exploit. Feel free to skip ahead to the next section by clicking here.

At this point, I was determined to find some heap object that I could re-allocate in place of other_sigqueue's slab page, and somehow use the arbitrary decrement primitive to leak a kernel text address. I spent quite a few hours on this step.

After scanning through a lot of objects, even though I saw many potential candidates, I couldn't think of a way to use the arbitrary decrement to leak an address. There was a copy_to_user() via copy_siginfo() if I used the dequeueing into a type confusion primitive, but it seemed very difficult to set up perfectly, and the kernel text pointer would have to be at a very specific offset...

So I shifted my focus to reference counts instead. If I could re-allocate other_sigqueue's slab page as some object that has a reference count, I could trigger a UAF on the other object easily. Unlike the previous arbitrary free avenue, this one seemed much easier and did not force any special requirements on the other object.

I started scanning through the kernel again, this time for any structures with reference counters that could be allocated out of kmalloc-256 or lower (kmalloc-512 uses order-1 pages, so it was out of the question), as well as all kmem_cache specific allocations that use order-0 pages.

Suffice to say, I came across many potential candidates (for example, struct file *). As I was looking through all the candidates, I couldn't help but be annoyed again at the thought of having to exploit another UAF on a completely new object. Even if there are more object types available to me now, surely there must be another, easier way to use the arbitrary decrement to gain root privileges?

At this point, I decided to take a break and come back a bit later. I continued to ponder on how I could use the arbitrary decrement primitive to decrement some kernel data somehow and have that lead to root privileges.

Important

If you're reading this, and you know of some reference counted object that would have been easy to exploit with by triggering a UAF on it, please let me know! I would love to learn more about this!

Luckily, it didn't take that long for me to think of the structure I ended up using in the final exploit.

Credentials Saves The Day

I had already come across struct cred when scanning the kernel for usable structures (explained in the previous section). However, it took me a while to connect the dots and realize that I could use the arbitrary decrement primitive to decrement the .euid field of a struct cred structure to 0, and then spawn a root shell out of it.

Additionally, since capabilities for a normal user struct cred are usually 0, I can decrement that and cause an integer underflow too, in order to gain full capabilities.

Initially, I actually tried to spray struct cred structures by using fork(), but as it turns out, fork() itself allocates multiple pages for the kernel thread stack before it ever allocates the struct cred, so that plan did not look like it would work, because I had no idea what the current struct cred active slab page looked like.

However, after looking at all the callsites of prepare_cred() (the function used to allocate struct cred structures), I realized that calling setresuid(-1, -1, -1) in a forked process was a perfect spray – it allocates one struct cred structure and just returns.

At this point, the final exploit plan was ready to go. I'll list out all the steps in the next section.

Final Exploitation Steps

It's been a long journey, but we're finally at the end. Since I've explained all the steps up until the "Cross-caching Back To The Page Allocator" section very clearly, I'll just touch on them briefly.

- Set up the parent and child process, plus any child threads required to trigger the vulnerability.

- Trigger the vulnerability in the child process -> free the

uaf_timer-> re-allocate it asrealloc_timerinside the parent process. - Call

timer_settime()in the parent process at just the right time to get theuaf_timer->sigqinserted into both the parent and child process's pending list. - Delete the timer and dequeue the

uaf_timer->sigqfrom the parent process. You will end up with an infinite reference to theuaf_timer->sigqin either the parent or child process's pending list. - After getting an infinite reference to

uaf_sigqueueinside a task's pending list, use the cross-cache exploitation technique to send its page back to the page allocator. - Re-allocate the page as a pipe buffer data page.

- Insert and dequeue signals from the task's pending list in a specific way to get heap leaks (explained in the "Getting Heap Leaks" section).

- It's particularly important to get the heap address of another real

struct sigqueueobject which I callother_sigqueue. The other leaks don't matter as much.

- It's particularly important to get the heap address of another real

- Prepare to perform a second cross-cache attack – this is intended to send

other_sigqueue's page back to the page allocator (I do it on a different CPU). - Before completing the cross-cache attack, use

fork()to create 1000 child processes and have them block on a pipe. - Free

other_sigqueue's page back to the page allocator now. - Wake up each forked child process (from step 5) one at a time, and have them call

setresuid(-1, -1, -1). This will allocate onestruct credstructure for each child process.- It's basically guaranteed that the

other_sigqueue's page will be reused for one of these pages ofstruct credstructures.

- It's basically guaranteed that the

- Use the arbitrary decrement primitive to decrement any one of the

struct cred'seuidfield to 0.- We already know the address of

other_sigqueue, and we know its page will have thesestruct credstructures in it.

- We already know the address of

- Wake up each forked child process one more time, and have them check their own EUID using

geteuid(). If it's not 0, have them report back and block forever. - Once the child with EUID 0 wakes up, have it call

setresgid(0,0,0)andsetresuid(0,0,0)before callingsystem("/bin/sh").

After the final step, you will be greeted by a root shell!

Conclusion

The final exploit is on my Github. Click here to go to the section that has the link and a demo.

I spent approximately 1.5 weeks analyzing and writing a full exploit for this vulnerability. It is by far the most intricate and complex exploit I've written. I'm pretty sure I'll start to forget details about the exploit within like a week, so if you want to ask me questions, please do so quickly! 😛

Overall, I'd say it was an amazing learning experience, and it's definitely re-affirmed my stance on using past vulnerabilities as a way to learn about new targets and subsystems in great detail.

In fact, I now know so much more about the following than I ever did before:

- CPU scheduler internals

- How processes and threads work

- How signals work

- How to detect and extend race windows

- Exploitation techniques in general

I highly recommend this approach for anyone wanting to dive into security research. If you're having trouble getting started, or if you just have no idea where to start, just pick a vulnerability and dive right into analyzing it.

You don't even have to turn it into a full exploit like I did! Just get started, and see where it takes you. Sometimes, that's all it takes.